By late 1969, Creedence Clearwater Revival were operating like a hit-making machine. In a single year, they’d already released Bayou Country and Green River, both massive successes that cemented their “swamp rock” identity. Yet Willy and the Poor Boys, their third album in ten months, somehow avoided creative burnout and expanded the band’s social and musical scope. It’s a lean, 35-minute masterpiece of American grit, class consciousness, and unstoppable rhythm — the sound of a working-class band chronicling a turbulent nation without missing the beat.

Themes & Concept

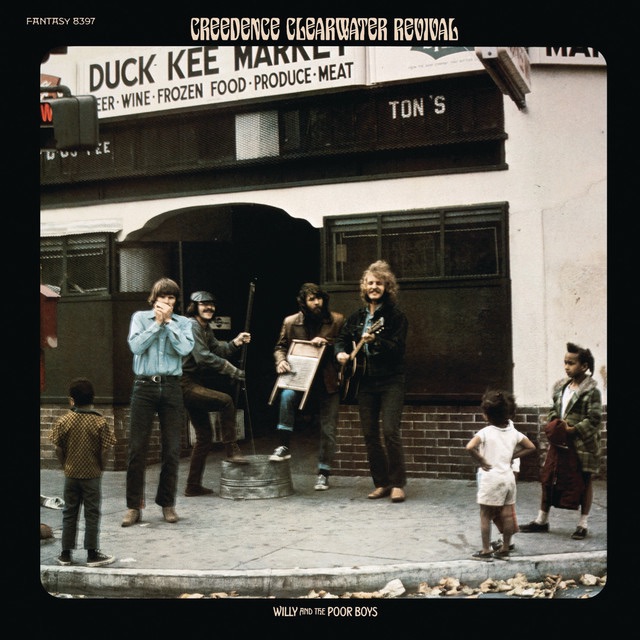

On paper, Willy and the Poor Boys seems almost conceptual: a tribute to street musicians and outsiders playing for spare change (“Down on the Corner”), contrasting the haves and have-nots (“Fortunate Son”), and celebrating a distinctly blue-collar Americana.

John Fogerty’s songwriting captures the pulse of 1969’s social unrest — the Vietnam War, wealth inequality, and the myth of the American Dream — yet filters it through CCR’s unpretentious Southern-rock storytelling. Even when Fogerty wasn’t making political statements, his characters — drifters, preachers, and the downtrodden — carried the weight of a country in flux.

Track-by-Track Highlights

“Down on the Corner”

The album opens with one of CCR’s most infectious grooves. Built on a percolating bassline and percussive guitar licks, it’s both a celebration of street performance and a meta-commentary on the band itself — “Willy and the Poor Boys” being Creedence in disguise. The hand-claps and joyous feel mask a subtle empathy for working-class artistry.

“It Came Out of the Sky”

A fast, witty rock-and-roll tale about a UFO landing in farmer’s fields, this track showcases Fogerty’s humor and gift for narrative songwriting. Beneath the chuckle lies a sly satire on media frenzy and religious opportunism.

“Cotton Fields” (Lead Belly cover)

CCR’s version turns the folk classic into a twang-filled, country-rock shuffle, bridging Mississippi roots music and California garage energy. It’s reverent without being academic — a testament to Fogerty’s love for the American songbook.

“Poorboy Shuffle” / “Feelin’ Blue”

An instrumental interlude and a deep blues groove, these two flow together seamlessly, reflecting the album’s street-band motif. “Feelin’ Blue” leans heavily on bass and harmonica, evoking juke-joint atmospheres with precision.

“Fortunate Son”

Arguably CCR’s defining protest anthem. Clocking in at under three minutes, it remains a concise indictment of class privilege and hypocrisy during the Vietnam War era. “It ain’t me, I ain’t no senator’s son” still cuts as sharply today as it did in ’69. Few protest songs have endured so well, balancing fury with dance-floor propulsion.

“Don’t Look Now (It Ain’t You or Me)”

A wry critique of the working class propping up the American elite, this song pairs biting lyrics with CCR’s signature swamp swing. It’s sociopolitical commentary disguised as bar-band boogie.

“The Midnight Special”

A traditional prison song made famous by Lead Belly, here given new life with Creedence’s muscular rhythm section and Fogerty’s gravel-tinged shout. It feels almost like a communal hymn — a call for freedom, spiritual and literal.

“Side o’ the Road” / “Effigy”

The closing pair shows the band’s range. “Side o’ the Road” is a tight instrumental rooted in Memphis R&B, while “Effigy” ends the album on a haunting, cinematic note — a slow-burn dirge about societal collapse and political decay. It’s as apocalyptic as CCR ever got, and a fitting finale for 1969.

Lyrics and Tone

Fogerty’s writing on Willy and the Poor Boys is deceptively simple: plain language masking profound commentary. He was no Dylan, but his directness was his strength — populist poetry for people who didn’t read Rolling Stone for philosophy. The lyrics are laced with empathy and anger, but always grounded in movement and melody.

The album also reflects a shift from pure swamp rock toward something broader — a blend of roots, blues, country, and proto-Americana that would influence artists from Bruce Springsteen to The Black Keys.

Musicianship

The band — John and Tom Fogerty on guitars, Stu Cook on bass, and Doug “Cosmo” Clifford on drums — was an astonishingly tight rhythm unit. They could swing like a Southern soul band and punch like a garage outfit. John Fogerty’s production keeps it raw: you can hear fingers on strings, air in the room, and the human imperfection that makes their records timeless.

⭐️ Legacy & Impact

Willy and the Poor Boys was both commercially huge (reaching #3 on the Billboard 200) and artistically defining. “Down on the Corner” and “Fortunate Son” became instant classics, but the album’s deep cuts — “Effigy,” “Feelin’ Blue” — reveal the band’s depth.

In hindsight, this record captures the end of the ’60s more accurately than most grander statements. It’s America at a crossroads: festive on the surface, fractured underneath. Its influence runs through decades of Americana, roots rock, and alt-country.

Final Verdict

★★★★★ (5/5)

Willy and the Poor Boys remains one of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s finest hours — a perfect fusion of protest, populism, and party music. It’s the sound of working-class resilience, built on riffs you can dance to and words that still sting half a century later.

“Fortunate Son” may have been the warning; “Down on the Corner” was the cure — finding joy, rhythm, and solidarity even when the world’s on fire.